When the boss of the company responsible for asylum accommodation in Hull appeared before MPs recently he kicked off his evidence with a big fat lie.

Jason Burt, group director of health, safety and compliance at housing group Mears, was speaking at the Home Affairs Select Committee as part of its current inquiry into asylum accommodation in the UK.

Mears might not be a household name but in January 2109 it was awarded three separate 10-year contracts by the Home Office to provide accommodation and support for asylum seekers in Scotland, Northern Ireland and the North East, Yorkshire and Humber (NEYH).

Back then, the contracts had been priced and awarded on the basis of only providing so-called dispersed community-based accommodation in traditional houses and flats.

However, as we all now know, the subsequent provision of hotel accommodation turned the contracts into very different - and hugely more profitable - beasts.

Giving evidence to the committee about Mears’ track record, Burt said: “When we pitched for the contract originally…..we did not factor in using hotels; hotels and the emergency contingency accommodation was something that we had to take on board as a result of the pandemic.”

That statement is quite simply wrong and wasn’t challenged at the committee. Sadly, this narrative was also repeated by Home Office officials at a subsequent meeting of the same committee last week.

So I guess it’s up to me to set the record straight because Burt’s pork pie helpfully puts the blame on Covid while hiding the reality of Mears switching to using “significantly more costly hotels” (Home Office 2024) several months before anyone had even heard about Coronavirus.

It also adds to concerns over the profit-driven nature of contracts handed to private companies dealing with what is, essentially, a social care issue.

More on these eye-watering profits later but it’s worth saying now they remain a central part of the privatisation of asylum accommodation started in 2012 under the coalition government. Until then, local councils co-ordinated accommodation using Home Office funding but that system was swept away and replaced with private contracts.

In 2012 the largest contract worth £211m over seven years went to security firm G4S, a company with no previous experience of housing vulnerable people. Inevitably, layers of sub-contracting followed, from smaller housing providers to individual private landlords.

What had been a public service was effectively turned into a commercial marketplace with companies at each layer of the cake looking to make money. In other words, profits over people.

The Mears contracts were among seven regional awarded to private firms by the Home Office in January 2019. They came into force on April 1 that year replacing the original G4S contracts.

Yet despite Burt’s claim that emergency contingency hotel accommodation was something Mears only brought in as a result of Covid-19, the company actually started housing asylum seekers in Hull’s Royal Hotel within five months of taking on the contract and six months before Boris Johnson announced the first UK lockdown to combat the threat of the new virus.

Why did Mears start placing people into hotels so soon after taking over the contract?

As the above timeline shows and contrary to Burt’s evidence, it had nothing to do with the pandemic. Instead, it was a hasty response to increasing numbers of asylum seekers entering the processing system and a lack of immediately accessible dispersed accommodation on Mears’ books.

Just as G4S had been criticised for being unprepared when taking on the previous contract seven years earlier, Mears was facing similar criticisms albeit in different circumstances.

How do I know this? Back in September 2020 Hull City Council submitted evidence to a Public Accounts Committee inquiry into the early months of the new asylum accommodation contracts.

It said: “The implementation of the new contracts appears to have coincided with a rise in asylum applications made in the UK, with some applications linked to Brexit and a perception that people may find it harder to settle in the UK in the future.

“The increase resulted in Mears deciding to use hotels as contingency asylum accommodation, with a hotel in Hull being used by Mears from 23/09/2019 – 26/03/2020, along with hotels in East Riding, and West Yorkshire; without prior consultation with local authorities including Hull, with 100-130 people placed in the Hull hotel at any one time, and without any planning for health screening and healthcare being in place.”

(The bold type isn’t mine, it was in the council’s submission).

It went on: “This was of significant concern for local authorities across the Yorkshire and Humberside area, including Hull and, in November 2019, Hull City Council’s Chief Executive was signatory to a joint letter with Hull Clinical Commissioning Group and East Riding Council of Yorkshire to the Home Office outlining very serious concerns about the management of asylum dispersal by Mears, and the use of hotels as asylum accommodation.

“The letter stated that the local authority would pause all refugee resettlement activity with effect from the 10th December 2019 and that this would remain the position until the Home Office fulfilled the certain conditions, including: ceasing use of hotels, funding and development of health services for asylum seekers in hotels, improving data sharing about asylum seekers to enable LA’s to meet their statutory responsibilities and consideration of impact of all Home Office programmes including LA resettlement activity and not just private contractors and asylum contracts, with a strategic assessment of asylum impact and a more equitable distribution of asylum seekers nationally.”

Pretty strong stuff and it was widely reported on at the time. I know this because I reported on the anger emanating from the Guildhall.

As it turned out, the complaints fell on deaf ears. The Home Office did nothing and Mears continued using the Royal Hotel for asylum seeker accommodation until 26 March 2020 - the day when Covid lockdown measures legally came into force.

The hotel was then emptied in anticipation of being used as potential key worker accommodation to support the response to Covid. However, that never happened.

Instead, asylum seekers were moved back in five months later after the Home Office informed the council that Mears would be providing 190 beds inside the building as a result of “extreme pressure on available bed spaces in the asylum system.”

On being notified, the council again raised “strong concerns” in a series of meetings and telephone calls with the Home Office. In addition, the city’s three MPs and the council leader wrote to the relevant government minister expressing their worries over the proposal.

The council’s submission to the subsequent inquiry captured some of these in the following way: “Concerns included: the fact that 190 people was the largest single placement in NEYH, potential impacts on Covid-19 transmission in the city (as the hotel is situated within the train station and transport interchange), the impacts of the need for on-going assessment, control and management of the situation in relation to the Covid Local Outbreak Management Plan, possible impacts on community cohesion with the placement of this number of single people in the city centre at a time of rising unemployment and local levels of poverty, pressures on health, CCG and LA, which are already feeling the impact of Covid-19 pandemic, and lack of support for asylum seekers by Mears Group.”

A council request for the process to be halted for a further risk assessment to be carried out and and management and support arrangements put in place was rejected. Instead, Mears said it was going ahead with the plan, albeit with a lower number of 130 asylum seekers.

The hotel has remained in use as asylum seeker accommodation ever since while other large local Mears-contracted sites at a former student halls of residence in Cottingham and the Humber View Hotel in North Ferriby have opened and closed, mirroring ebbs and flows in Home Office demand for places.

That demand has come at a cost. In 2020 the average accommodation cost per asylum seeker to the Home Office was £17,00 per year. In 2024 it had grown to £41,000.

Almost all of this increase wad attributable to an increased use of hotels. Whereas the per person per night cost of community-based dispersed accommodation is around £20, the average equivalent cost for a hotel is £158.

Perhaps this partly explains why The Royal Hotel remains in use for asylum seeker accommodation despite pledges by successive governments to reduce and eventually end the use of hotels. As Labour MP Chris Murray put it at the most recent select committee hearing: “Where is the incentive for contractors to stop using hotels when they are making so much money for them?”

When it was first awarded, the value of Mears’ 10-year NEYH contract was £0.8 billion. The latest Home Office estimate has adjusted that value to £1.5 billion.

A recent report by the National Audit Office on the asylum accommodation contracts revealed a combined total profit between all three main suppliers of £383m over the first five years. According to the NAO, Mears’ average reported profit margin on the NEYH contract over the period was 7%.

Each regional contract has a profit-sharing clause but, as yet, not a penny has been paid back to the Home Office despite thresholds meant to trigger annual repayments being exceeded seven times. An independent audit commissioned by the Home Office last year to check each companies’ financial results is expected to conclude soon.

Giving evidence, Mears’ Jason Burt challenged the figures in the NAO report. He said: “Our profit margin over the existence of the contract is actually in the region of our announced range of 5% to 6%. I acknowledge that the NAO report contained some figures in excess of that range, but it is important to note that those figures do not take into account the degree of profit that needs to be paid back in terms of the profit share.

“Each region is looked at on an independent basis in terms of performance. Of those three contracts, we are in profit in two and in underage in one - Scotland. Overall, our net margin is in the region of 5% to 6%, and we have in the region of £13.8 million to come back in profit share, which is the figure that we have given to the Home Office, and it is currently undergoing the audit process.”

Even with the profit share arrangement, Mears’ asylum seeker contracts have undoubtedly boosted the company’s finances. Its latest annual report for 2024 published in April recorded a 37% increase in pre-tax profits to £64.1m compared to the previous year. In somewhat of an understatement, Mears’ chairman Jim Clarke noted: “The group has experienced elevated revenues within its asylum services.”

Then there are the profits being made by Mears’ sub-contractors, who range from hotel groups to transport companies and security firms.

According the NAO report, 33 sub-contractors are being used by Mears across its three regional contracts.

So what lies ahead for the Royal Hotel? Mears’ contract runs until 2029 although there is a break clause coming up next year. The current Labour government says ending hotel use is a priority with asylum minister Angela Eagle saying she would like to see a new model featuring greater involvement with local councils.

In the meantime, councils have been invited to submit expressions of interest in offering alternative accommodation to hotels in their areas. So far, nearly 200 sites have been suggested across the country.

Eagle’s push to bring back more local accountability into the operation asylum accommodation has to be welcomed. Successive inquiries into the issue have highlighted how local councils have been consistently sidelined and ignored by private contractor suppliers and the Home Office until only relatively recently.

Evidence submitted to the current inquiry has also underlined how much of the Home Office’s time and resources have been eaten up on failed initiatives such as procuring large sites like RAF Scampton, using the floating Stockholm Bibby barge and attempting to send asylum seekers to Rwanda. These have all diverted staff away from doing the basic bread and butter day job of actually processing asylum applications and moving people through the system.

Needs to say, much of this log jam was the result of brash promises made by the likes of Boris Johnson, Priti Patel and Suella Braverman. Thankfully, Angela Eagle is testimony to the fact that at least some sensible people are now pulling the political levers.

However, whether she delivers remains to be seen and that includes finding an alternative to using venues like Hull’s Royal Hotel.

For nearly six years, the hotel has been virtually isolated from its immediate surroundings. For all the profits it has generated for the likes of Mears and numerous sub-contractors, its negative impact on the economy of the city centre and Hull has been immense.

You don’t have to be a genius to work out that the spending power of an asylum seeker on a weekly allowance of £8.86 doesn’t come remotely close the spending power of typical hotel guest staying there prior to September 2019.

The original council submission also highlighted a “focus” on the hotel from far-right groups, culminating in a protest and counter-protest on 29 August 2020 - four weeks after asylum seekers returned to stay there.

Sounds familiar? Four years later the hotel would become the focal point of a mass riot during unprecedented scenes of violent disorder in the city centre.

Once again, the resulting negative impact from that day on Hull’s image can’t be overstated enough.

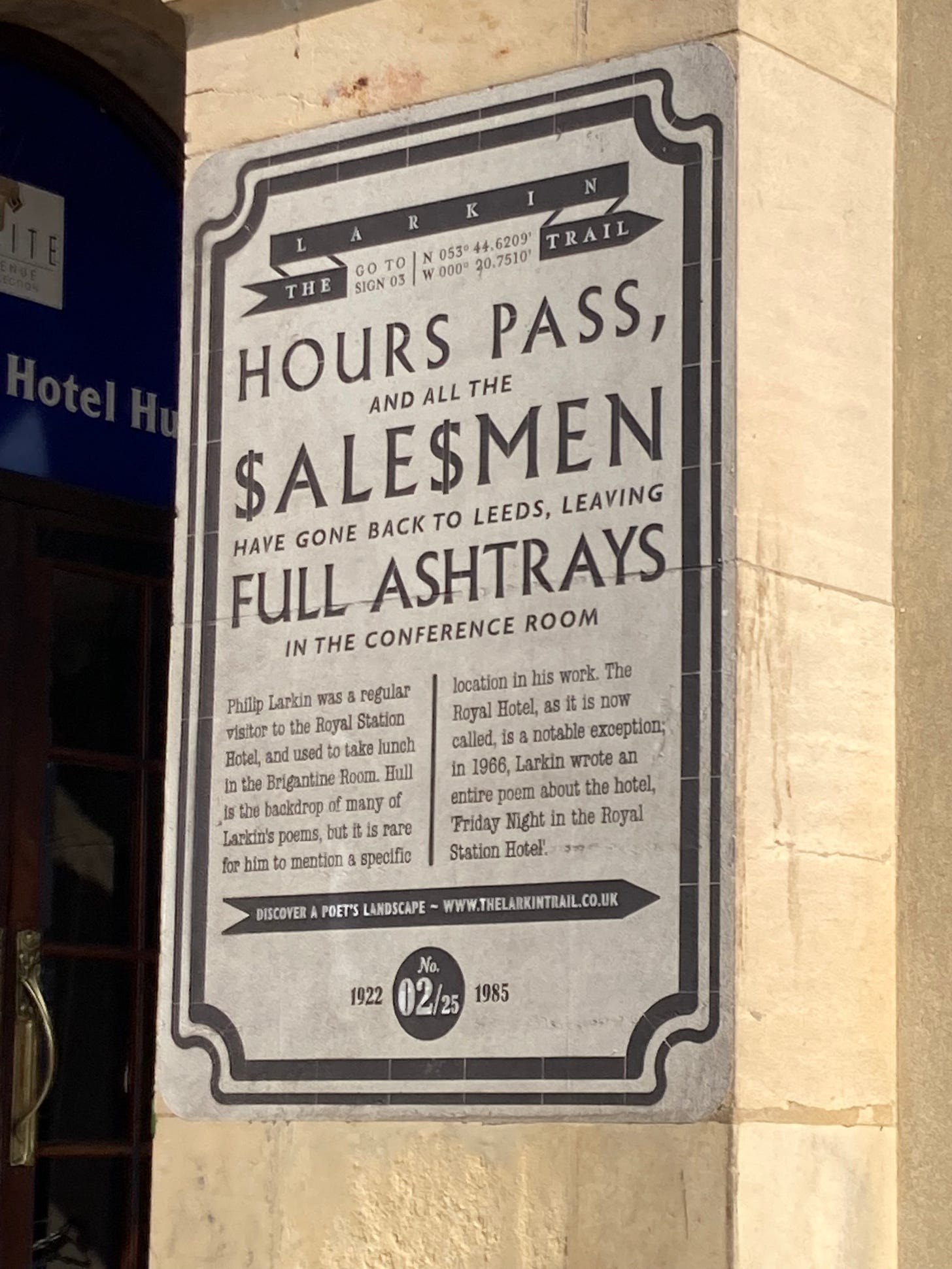

Until its change of use in 2019, the Victorian landmark had been attracting renewed positive attention as one of the favourite places of the late poet and Hull University librarian Philip Larkin.

A statue of Larkin on the railway station concourse near the hotel’s entrance was unveiled in 2010 to mark the 25th anniversary of his death. It imagines him rushing from the hotel for a waiting train.

Meanwhile, a plaque neatly the hotel’s entrance on Ferensway commemorates his celebrated poem Friday Night at the Royal Station Hotel.

Written in 1966, it paints a desolate picture of an empty hotel. Without its guests, Larkin suggests the place has no real meaning, existing in a semi-twilight world of silence and loneliness.

Instead of his departed salesmen from Leeds, the hotel now hosts invisible homeless travellers from around the world providing a new take Larkin’s atmospheric ode to human dislocation.

It might be an unusual way to end proceedings but here’s the poem in full. Sit back, soak up his words and I’ll see you next week.

Light spreads darkly downwards from the high

Clusters of lights over empty chairs

That face each other, coloured differently.

Through open doors, the dining-room declares

A larger loneliness of knives and glass

And silence laid like carpet. A porter reads

An unsold evening paper. Hours pass,

And all the salesmen have gone back to Leeds,

Leaving full ashtrays in the Conference Room.

In shoeless corridors, the lights burn.How

Isolated, like a fort, it is -

The headed paper, made for writing home

(If home existed) letters of exile: Now

Night comes on. Waves fold behind villages

Following on from what Steve said, in the sense of when we pitched for the contract originally, from Mears’ perspective I would just add that we did not factor in using hotels; hotels and the emergency contingency accommodation was something that we had to take on board as a result of the pandemic. There are greater challenges and increased costs associated with the use of hotels, but our perspective in terms of our approach to contractual pricing for the hotels and DA is neutral, or the same.

Is it a mistake not to allow asylum seekers to work?

Even if they are offered accommodation in places like this there’s is work needed to provide that accommodation. I know there are arguments about undercutting the wages with cheap labour - but proper enforcement of minimum wage regulations would deal with that)

Allowing people to work would be one of the best ways of integrating people into society surely - especially if their colleagues were giving feedback as part of their asylum process.

Profiteering & exploiting people in desperate circumstances, often fleeing from places we’ve bombed to hell, shouldn’t be allowed.

And yet here we go again with Iran.

Commodifying asylum seekers as an item in a profit based contract is fundamentally immoral. Each individual will have complex and challenging needs that require a multi-agency approach, not being dumped in soulless hotels unsuited for the purpose to contribute to the profits of the provider. Our treatment of asylum seekers in this country is a national disgrace. Congratulations Angus in so meticulously documenting it.